Aberrated Image Recovery of Ultracold Atoms#

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns; sns.set()

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import scipy as sp

import skimage as ski

import sklearn as skl

from sklearn import cluster

Overview#

Overview#

Over the past 20-30 years the groundwork has been laid for precise experimental control of atomic gases at ultracold temperatures. These ultracold atom gas experiments explore the quantum mechanics of their underlying atomic systems to a diverse set applications ranging from the simulation of computationally difficult physics problems [1] to the sensing of new physics beyond the standard model [2]. Most experiments in this field rely on directly imaging the ultracold gas they make, in order to extract data about the size and shape of the atomic number density distribution being imaged.

The goal of this project is to introduce you to some relevant image processing techniques, as well as to get familiar with an image as a data element. As you will demonstrate, images are a kind of data with a very large number of features, but where almost all of those features within some region of interest are highly correlated. Of interest in this project is how the effects of real imaging systems distort the information contained in an image, and how those effects can be unfolded from the data to recover information about the true density distribution.

Capturing all possible kinds of aberrations and noise present in real experimental data of ultracold atom images is outside the scope of the simulated test data in this project. Instead, we limit ourselves to one key effect: optical aberrations due to the finite nature of a real imaging system’s depth of field.

Data Sources#

File URLs

You should untar this file into your local directory and access the image files from there:

Heavy_tails/HiNA.atom_num=100000.*.tiffNumber_estimate/LoNA.atom_num=10000.*.tiff

Also included is ImageSimulation.ipynb, which is the notebook used to generate the data you will find in that folder. You are encouraged to read through that notebook to see how the simulation works and even generate your own datasets if desired.

You are welcome to access the images however works best for you, but a simple solution is to download the dataset folder to the same path as this notebook (or the one you plan to do your analysis in) and use the following helper function to important an image based on the true parameters of the underlying density distribution—found in the image file name.

def Import_Image(dataset_name, imaging_sys, atom_number, mu_x, mu_y, mu_z, sigma_x, sigma_y, sigma_z, Z04, seed):

"""Important an image following the project file naming structure.

:param dataset_name: str

Name of the dataset.

:param imaging_sys: str

Name of the imaging system (e.g. 'LoNA' or 'HiNA').

:param atom_number: int

Atom number normalization factor.

:param mu_x: float

Density distribution true mean x.

:param mu_y: float

Density distribution true mean y.

:param mu_z: float

Density distribution true mean z.

:param sigma_x: float

Density distribution true sigma x.

:param sigma_y: float

Density distribution true sigma y.

:param sigma_z: float

Density distribution true sigma z.

:param Z04: float

Coefficient of spherical aberrations.

:param seed: int

Seed for Gaussian noise.

:return:

"""

dataset_name = dataset_name + '\\'

file_name = imaging_sys + '.atom_num=%i.mu=(%0.1f...%0.1f...%0.1f).sigma=(%0.1f...%0.1f...%0.1f).Z04=%0.1f.seed=%i.tiff' % (atom_number, mu_x, mu_y, mu_z, sigma_x, sigma_y, sigma_z, Z04, seed)

im = ski.io.imread(dataset_name + file_name)

return im

Questions#

Question 01#

What is a cold atom gas? How cold are we talking? How do experiments bring atoms down to these temperatures?

When you research these experiments you will find that the Alkali atoms (Rb, K, Na, etc.) compose the majority set of species used. Why these atoms? Hint: recall high school chemistry. What do these atoms have in common with everyone’s favorite quantum system, the hydrogen atom?

A helpful resource is Foot’s Atomic Physics [3].

Question 02#

When attempting to measure the number density distribution of cold atom gas in experiment, we typically release the gas from any kind of confinement and let it expand in free-fall before taking an image at some time-of-flight (TOF). When we take a picture thereafter the density distribution often has the shape of Gaussian. Why is that? Think stat mech.

Question 03#

Real imaging systems have a finite resolution set by the diffraction limit. Given a point source emitting a spherical EM field, a real lens will propagate the field from the object plane to the imaging plane, projecting a pattern which we call the imaging response function, or point spread function (PSF), of the system. For any object with finite size, we can think of the resultant image as being formed by a sum over the PSF associated with each point in the object, i.e. a convolution.

For a circular lens the shape of the best focus PSF (meaning the shape of an image formed from a point source located on the imaging axis at the best focus) we refer to as the Airy disk. Its first set of zeros are located at \(\rho\approx3.83\), for a dimensionless radial component \(\rho\).

Given this information and the functional form of the Airy disk, estimate the amount of irradiance (or weight) that sits in the central peak of the pattern relative to the whole distribution.

If you were to approximate this distribution to a Gaussian with the same peak irradiance, how would the first minima of the Airy disk relate to the \(1/e^2\) waist of the Gaussian distribution?

In addition to provided links, another useful resource is Goodman’s Introduction to Fourier Optics [4].

Questions 04#

In the previous question the resolution we were interested in describes the size of the image of a point source in the plane transverse to the axis the image propagates along. What about along the imaging axis? We often calls this axial resolution the depth of field (DOF), although when we want a number to describe it different sources define that value differently.

How are the DOF and transverse resolution related to each other? No mathematical relationship is necessary here (although you can if you want to, so long as you restrict yourself to thinking about the axial PSF along \(\rho=0\)).

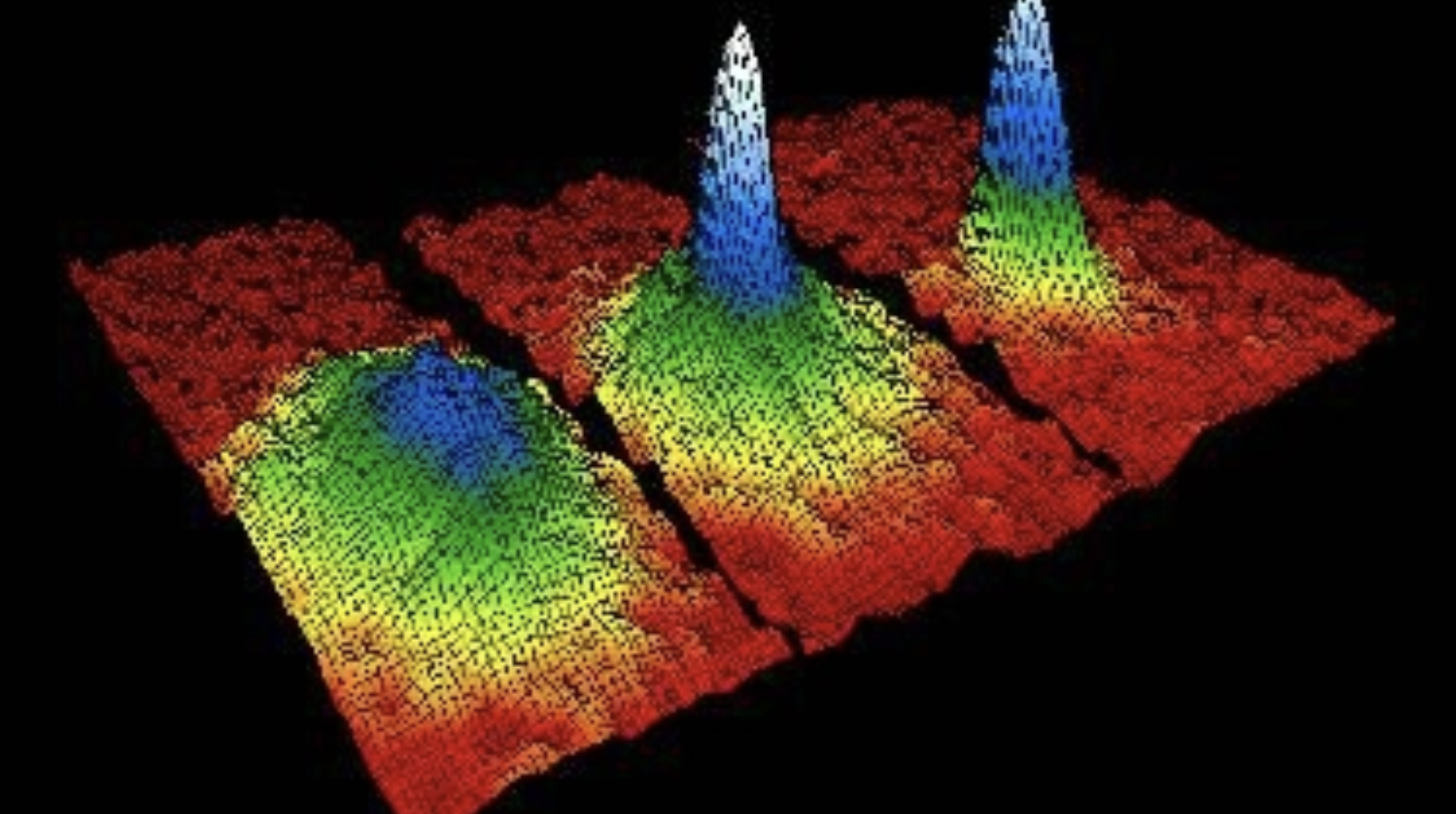

To answer the rest of the questions, we will use images from the Heavy_tails datasets. These images depict cold atom gases of variable \(\sigma_{xy}\) and \(\sigma_z\) at an arbitrary atom number. Half of the images contains data representing isotropic gases (those where \(\sigma_{xy}=\sigma_z\)), while the other half represent images of gases elongated along the imaging axis (where \(\sigma_{xy}<\sigma_z\)). You will note I am discussing the size of distribution along the imaging axis. Images are 2D objects, but in reality they represent a volume of light collected by the imaging system. The irradiance in these images represents a 2D column density of the original atomic number density, where the imaging system has integrated over that density distribution that lies along the imaging axis. For a 3D Gaussian number density, you might think this is not an issue. You will see that the influence of the imaging system has the potential to distort the image in certain cases.

The data assumes that images are collected by a moderately high NA=0.4 objective lens, and projected on to a sensor with a pixel resolution PS=13 um, by an \(M=20\times\) telescope. The high resolution of this objective lens leads to a short DOF. For images in the dataset of these elongated gases, you will notice a visible halo around the central peak of the gas. This an effect caused by the defocused fields propagated off of atoms in the distribution outside the DOF. The goal of the questions below are to estimate what the underlying number density distribution looks like with this halo (which should appear the same between the elongated and isotropic images, with and without the presence of these aberrations, respectively).

Question 05#

The data here in this project are images—2D arrays containing greyscale information of the irradiance associated with the image of the gas. What is the dimension of this kind of data? Why is the not problem considering the kind of data features we are interested in?

Quesiton 06#

For all the images in the dataset, use singular value decomposition (SVD) to generate a compressed version of each image, by decomposing the data and sampling a rank-\(k\) subset of the latent variable space. Reconstruct images for a handful of \(k\).

At what point do images with the same \(\sigma_{xy}\) but different \(\sigma_z\) appear to have the same sized tail in the compressed parameter space?

Question 07#

Thanks to our understanding of the physics in these images, we know the true number density distribution reflected is that of a Gaussian. The halo present in some of these images of elongated gases, however, makes it difficult to estimate true transverse size of the gas, \(\sigma_{xy}\). Because we know the family of function in which the solution lives, this make variational Bayesian inference an appealing tool to tackle the problem.

Let \(p\) represent the density distribution representing in an image. By either estimation of second of moment or curve-fitting (see ImageSimulation.ipynb for examples), define a reasonable family of 2D Gaussian distributions, \(q(\sigma)\), that spans the possible solutions of the true \(\sigma_{xy}\) for each image. Calculate \(\text{KL}(q(\sigma)||p)\) and attempt to minimize it over \(\sigma\). It is sufficient for this question to estimate divergence via numerical integration. If numerical integration take a long time, consider using a sufficient rank-\(k\) reconstruction of the image from the previous question.

How do your results compare to the initial estimates you obtained to define the family \(q(\sigma)\)? How about with the true \(\sigma_{xy}\) listed in the file name?

Question 08#

Black Box Variational Inference allows one to solve the same optimization problem as the methods above, without the need for the computational costs associated with the analytical (or numeric) estimation of the KL divergence or \(\text{ELBO}(q)\), instead opting to perform a stochastic optimization of the gradient of \(\text{ELBO}(q)\) [5]. Read through [5] and implement a similar algorithm to estimate \(\sigma_{xy}\).

How does this compare with your answers to question 7?

References#

[1] S. S. Kondov, W. R. McGehee, J. J. Zirbel, and B. DeMarco, Science 334, 66 (2011).

[2] W. B. Cairncross, D. N. Gresh, M. Grau, K. C. Cossel, T. S. Roussy, Y. Ni, Y. Zhou, J. Ye, and E. A. Cornell, Physical Review Letters 119, (2017).

[3] Goodman, J. W. (2005). Introduction to Fourier optics. 3rd ed.

[4] Foot, C. (2005). Atomic physics. Oxford University Press, USA.

[5] R. Ranganath, S. Gerrish, and D. Blei, 10.48550/arXiv.1401.0118, (2013).

Acknowledgements#

Initial version: Max Gold with some guidence from Mark Neubauer

© Copyright 2024